content notice for this issue: genocide in Palestine, Alabama’s anti-IVF policy, risk of fetal demise

There is a particular kind of grief, being disappointed by people who you love.

There is a particular kind of despair, bearing witness to the loss of humanity in another.

There is a particular kind of anguish, searching for more words to describe devastation.

There is a particular kind of heartache, working systems from within unsure if the working is working and still believing the possibility of it working it worth it.

There is a particular kind of agony, watching the steady increase of numbers missing, known killed, how many children, how many patients, how many journalists, how many healthcare workers, how many artists, how many newborns, how many entire families, how many. And how many more.

There is a particular kind of religious, epistemic, and physiologic violence in a forced famine coinciding with a month of fasting as a religious rite during Ramadan.

There is a particular kind of desperation, knowing our pain is in service to their freedom.

Cognitive dissonance can feel irreconcilable, until we resolve ourselves firmly in all of the ways our humanity is bound with one another. All of the ways our liberation is collectively interdependent. All of the ways our speaking up allows others to do so. This means seeing people we previously respected, appreciated, and aligned with in a different way and, for that, I offer you the language above, realizing in my own life there has been and will continue to be incredible grief, despair, anguish, heartache, agony, epistemic violence, and desperation in my work to continue calling what is happening in Palestine a genocide, calling for an immediate and permanent ceasefire, and chanting for a free Palestine.

For more, I offer the following:

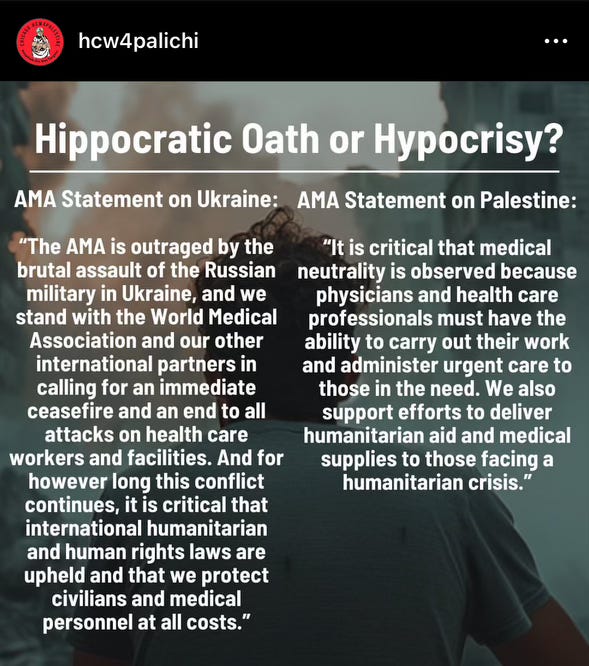

@hcw4palichi recent carousel detailing the double standard of healthcare organizations speaking up for Ukraine but not for Palestine - if this has also been you, please take time to yourself to consider why, what that means for how you view humanity, and how you might realign.

We Are Not Okay: Moral Injury and a World on Fire by Keisha Ray for the American Journal of Bioethics

“…While a concept of moral injury based on the four broad ethical principles in health care—autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and social justice—has been suggested, the focus has remained on health care providers; in particular how witnessing violations of ethics makes them susceptible to harm, or moral injury (Heston and Pahang Citation2023). And while many bioethicists like myself don’t specifically work with patients and are not clinicians, our work is on the human condition. We often ask “What does it mean to be human and what does it mean to violate our humanity? What do humans need to lead a life of wellness and happiness?” To answer these broad questions and the endless specific questions they inspire, many of us apply the four biomedical principles—autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice—to our work. We also often create our own principles as well, by which to do bioethical work examining the human condition. Furthermore, as an applied field of study, we often take these principles, use them to call out instances of human rights violation, and offer practical solutions…

At some point, though, it will become too much (For many, it has already become too much). We will succumb to the injury of seeing our principles violated and televised for the world to see and feeling like it is only getting worse. Because at the heart of moral injury is our own humanity. We can only take so much. We can only keep working for so long amid tragedy, violence, death, and destruction without a light at the end of the tunnel. Being a human in a world ablaze makes us susceptible to moral injury, regardless of profession…

The doctor’s role in liberation: an interview with Dr. Ghassan Abu-Sittah by Mary Turfah for Mondoweiss

I urge you to read the interview in its entirety - here is a brief excerpt.

“…It’s not about the medicine, but rather about what medicine allows you to do, that immediate ability to reach into people’s lives and to reach into their struggle and to see up close. Medicine allows you to stand at the coalface, and politics allows you to see what you are looking at. That’s what shapes that kind of medical activism, if you want to call it that, or medical liberation ideology.

Yeah, we’re taught to keep politics outside of medicine in a way that would be laughable for any other field, the expectation that you not invest in the people that you’re working with. And it seems there isn’t that same hang-up somehow in Palestine.

I saw the National Health Service prior to this creeping corporatization and privatization, and I think this idea, this laughable idea about politics and health, is a way to ensure the commoditization of health, which is an anathema and a bizarre concept which corporatization of medicine relies on—it goes unchallenged. You can’t bring politics into medicine, but medicine is all about politics. Whether the consequences of politics in terms of people’s health, or the consequences of politics in terms of what you can deliver to whom—it’s a critical component of medicine…

…One last question, where are you anchoring hope?

Oh, in Gaza. Absolutely…”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to FM Weekly to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.